Black Roots: Everett Fly Delivers Frederick Law Olmsted Lecture at Harvard University

by Sydney Boyd, Humanities in American Life project manager

When he was in college at the University of Texas at Austin in the 1970s, Everett Fly took lots of courses on architectural history—everything from Egyptian, Roman, and Renaissance to Gothic and modern. Not one mentioned anything that Black people had planned, done, or created.

When he was in college at the University of Texas at Austin in the 1970s, Everett Fly took lots of courses on architectural history—everything from Egyptian, Roman, and Renaissance to Gothic and modern. Not one mentioned anything that Black people had planned, done, or created.

“In fact, Black people were not mentioned in any role in building or construction,” Fly said in his delivery of the annual Frederick Law Olmsted Lecture, “American Cultural Landscapes: Black Roots and Treasures,” presented virtually by Harvard University Graduate School of Design (GSD) and recorded on October 27, 2020. Humanities Texas, for which Fly formerly served as chair of the Board of Directors, featured the lecture in a January, 2021 article.

Looking for African American architectural history where others said there was none became a recurring—but formative—occurrence in Fly’s education and professional career. As a graduate student at GSD, Fly took one more history class, “Built American Landscape Since 1865,” a supposedly comprehensive account of westward settlements, roads, town squares, burial sites, and strip development taught by J.B. Jackson.

“He only mentioned that Black slaves had worked on Southern plantations and settled in rural villages when they were emancipated in 1865,” Fly said. “This raised my rebellious curiosity.”

Fly chose to write his term paper on the existence of Black towns and settlements. Even as Jackson warned him he wouldn’t find anything, he also offered to help Fly. One of Jackson’s teaching assistants got him a pass to access the library’s rare books collection, and Fly went to work.

“Bit by bit, I was able to find enough documentation on thirty or forty Black communities, including Tuskegee, Alabama; Mound Bayou, Mississippi; Hobson City, Alabama; and Eatonville, Florida. I collected enough to submit a coherent paper and thought I had proved my point—that African Americans had even built towns,” Fly said.

In 1977, Fly became the first African American to earn a master of landscape architecture degree from Harvard. Fly has since earned numerous prestigious awards—in 2014, the National Humanities Medal to name just one—he has served on an array of boards (including the Federation of State Humanities Councils’ from 1991-1994), and continues to uncover and celebrate architectural accomplishments of Black Americans, namely a database and archive detailing 1,200 sites and counting.

The “last stop” in Fly’s lecture was San Antonio—a city that Fly said has never had African Americans make up more than 10 percent of its population. When someone told him a few years ago that there was no Black history in San Antonio, Fly started combing through records.

“I began to search in the Bexar County Spanish archives and found cattle brand certificates that go back to the Spanish colonial time. Using multiple types of information—oral history, maps, and documentation—I was able to locate where Black folks owned farms, ranches, or had pastures for cattle,” Fly said. “…So far, I’ve come up with more than seventy-five certificates that were filed by African Americans. Five of those were filed by Black women.”

“I began to search in the Bexar County Spanish archives and found cattle brand certificates that go back to the Spanish colonial time. Using multiple types of information—oral history, maps, and documentation—I was able to locate where Black folks owned farms, ranches, or had pastures for cattle,” Fly said. “…So far, I’ve come up with more than seventy-five certificates that were filed by African Americans. Five of those were filed by Black women.”

Learn more about Fly’s story and life work by listening to the lecture in full at the Humanities Texas news page.

Photo Credits:

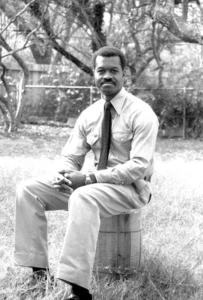

Photo 1: Portrait of Everett Fly, ca. 1988. Courtesy of Everett L. Fly.

Photo 2: Grace United Methodist Church and cemetery, Brazoria County, Texas. Courtesy of Everett L. Fly.

This post is part of “Humanities in American Life,” an initiative to increase awareness of the importance and use of the humanities in everyday American life.